Pourquoi le Canada accuse-t-il un si grand retard avec l’énergie géothermique

Il y a un très grand potentiel à développer des sources d’énergie naturelle sous la terre, mais les investissements et l’absence de volonté ferme a nui à leur développement.

La vapeur qui s’échappe des sources chaudes est la seule trace des richesses aquatiques qui se promènent sous la terre dans la région de Terrace en Colombie-Britannique. Au printemps toutefois il pourrait y avoir de nombreux indices que les humains se mettent à donner de l’importance à ces sources d’eau. Ce sera à ce moment que le personnel de Borealis GeoPower de Calgary commencera à percer une série de trous étroits allant jusqu’à 3,5 km dans la croûte terrestre pour trouver des sources d’eau très chaude.

Ce projet est encore en phase exploratoire. Au cours des prochains mois, les choses pourraient changer et on pourrait assister au développement de la première source commerciale d’énergie géothermique du pays.

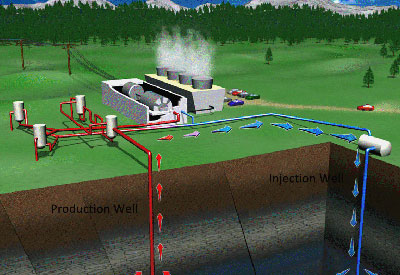

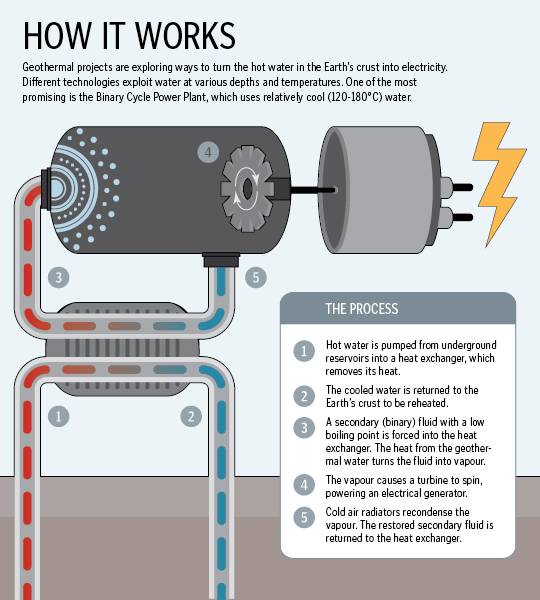

L’énergie géothermique est générée en utilisant la chaleur que l’on trouve naturellement dans les roches et profondément dans le sol. La production d’énergie géothermique utilise la vapeur capturée directement ou indirectement de la chaleur pour activer une turbine qui produira ainsi de l’électricité. La majorité des installations géothermiques fonctionnement dans un système fermé, alors que l’eau qui est extraite de la terre retourne tout de suite dans le sol après avoir été utilisée pour produire de l’électricité et être ainsi réutilisée pendant des décennies.

Plus de 80 pays sont actifs dans le développement de cette forme d’énergie électrique. L’industrie dans sa globalité a maintenant une capacité supérieure à 12 000 MW, suffisamment pour fournir l’électricité à 12 millions de maisons.

There is great potential to deploy the natural energy sources beneath the ground, but economics and lack of will have stalled development.

The steam rising from nearby hot springs is still the only real trace of the liquid treasure that flows deep underneath the Lakelse region south of Terrace, British Columbia.

By springtime, however, there are likely to be a lot of manmade clues signifying the springs’ growing importance. That’s when crews with Calgary-based Borealis GeoPower expect to begin drilling a series of narrow holes up to 3.5 kilometres into the Earth’s crust in a bid to find super-heated water.

The project is still in the early exploration phase. But the next few months could mark a major turning point in what’s been a long and heavily bureaucratic battle to develop the country’s first commercial geothermal power plant.

Depending on what they find underground, it also promises to be a satisfying ‘I-told-you-so’ moment for those who feel Canada has been too slow to invest in the next generation of renewable energy.

“We are pretty determined,” said Tim Thompson, Borealis CEO. “We think the government has missed the boat, broadly speaking, on the geothermal opportunity and we would love to prove them wrong.”

Geothermal energy is generated using the naturally-occurring heat found in rocks and liquid deep underground. A geothermal power plant uses steam captured directly or indirectly from the heat to drive a turbine, which, in turn, produces electricity. Environmentalists have long championed the renewable nature of the process. Most geothermal facilities operate on a closed-loop system, where the extracted water is pumped directly back into the ground after it’s been used for electricity production, and can be reused for decades.

More than 80 countries, led by the United States, Iceland and Mexico, are actively involved in geothermal electricity development. The global geothermal industry has now surpassed a capacity of 12,000 megawatts (MW), enough to power 12 million homes.

Geothermal’s growing popularity has much to do with its reputation as a clean and reliable energy source with a relatively small environmental footprint and little of the emissions produced by other energy sources, such as coal and oil.

In France, where a new network of deep wells under Paris is under construction, geothermal is seen as a safer alternative to the aging nuclear industry. Paris already has the largest concentration of geothermal facilities in Europe, delivering power and heat to residential homes, schools and offices. French industry advocates measure the country’s current geothermal electricity capacity at 16.5 MW. The national plan is to reach 80 MW by 2020.

Oregon, meanwhile, opened its first commercial geothermal plant, a 22-MW facility in the Neal Hot Springs, in 2012. The plant supplies about 24,000 homes on the Idaho power grid.

Energy experts say Canada has the potential to be a global leader in geothermal power production. The Canadian Geothermal Energy Association (CanGEA), a non-profit advocacy group, estimates the country could produce 5,000 MW of geothermal power by 2025. That’s enough to power five million homes and replace the installed coal-fired power plant fleet in Alberta, as well as all of the coal- and natural-gas-fired power plants in Saskatchewan, CanGEA says.

Yet Canada has virtually no commercial power facilities planned. The handful of proposals that are on the books, including the Lakelse project, are years from completion.

Michal Moore, professor of energy economics at the University of Calgary and visiting professor at Cornell University, said Canada’s geography is one of the biggest challenges. The Northwest Territories, Yukon, Alberta and parts of eastern Canada all have potentially good subsurface heat resources, but the effort it takes to reach them makes many projects cost-prohibitive, with no guarantees the water will be hot enough to use in power production.

To produce electricity efficiently, geothermal operations typically require access to a reservoir reaching at least 80 degrees Celsius.

But, with the limitations of current technology, Prof. Moore said it really only makes sense for companies to look for water in the range of 150 degrees Celsius or more. Given that restriction, only the northeastern region of BC offers any real promise for development.

“It’s not the only place to go for power, but it is the easiest one,” he said.

Money is another significant barrier. Comparatively low costs for hydroelectricity and fossil fuels have made geothermal exploration less attractive to investors leery of funding a risky start-up.

“If you are going to invest in geothermal or oil and gas, you are going to pick oil and gas first,” said Jason Switzer, national director of consulting and projects with the Calgary-based Pembina Institute.

Alison Thompson, chair of CanGEA, wants the federal and provincial governments to stop dragging their heels and deliver the policy and financial support the industry needs. Right now, Thompson said, geothermal projects flounder in a near-vacuum of political direction, noting most provinces lack the policy framework for dealing with who owns the subsurface resource and how to regulate it. Meanwhile, renewables such as wind and solar have flourished.

Tim Thompson, who calls geothermal “the best untouched resource on the planet,” said his company is committed to bringing the Lakelse project to reality.

The company is partnered with Enbridge and the Kitselas First Nation in the development. The consortium, LL Geothermal Inc., has so far paid about $100,000 to the province for exclusive geothermal subsurface rights to 2,865 hectares of land south of Lakelse Lake. The goal of the project is to generate 15 MW of electricity for the B.C. grid by 2018.

Source: GE Reports, https://gereports.ca.